‘COVID-Zero’: Can We Afford It?

‘COVID-Zero’: Can We Afford It?

By A. F. Cannon,

Writing for RealTimeCEO

The Australian government’s lockdowns and COVID-Zero policies have saved many lives, yet they cost our economy tens of millions of dollars a day. With all the uncertainties surrounding the pandemic’s future, can our current approach continue? This article looks at the health and economic implications of Australia’s policies.

I. The Cost of COVID-Zero

It is late August 2021 and over half of all Australians have been forced into lockdown.[1] After nearly a year and a half of the COVID pandemic, most citizens of NSW, Victoria and the ACT are once again confined to their houses; other states are prepared to enter snap lockdowns if a single new COVID-19 case emerges. In the worst afflicted of all states, NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said her fight against the ‘diabolical’ COVID Delta variant is ‘literally a war.’[2] Days later she imposed a curfew upon people in her state’s worst afflicted areas.[3]

The new round of lockdowns is a result of what some have called Australia ‘COVID-Zero’ policy.[4] Since July 24th last year, Australia has pursued an aggressive suppression[5] strategy to control the COVID-19 outbreak. An alternative to absolute elimination, controlled transmission and ‘do nothing’ approaches,[6] we use hard, early lockdowns to suppress the virus’s spread. It aims to stop community transmission and involves significant restrictions on international travel, social gathering, dining out. It also includes mandates for social distancing and mask-use.

Whatever the health benefits of the lockdowns, the COVID-Zero policy comes with obvious and significant economic costs: lockdowns make lots of business activities impossible. Economists estimate our COVID-Zero lockdowns cost the local economies in Brisbane and Melbourne around $100 million a day; in Sydney, they cost over $140 million. By constraining our commercial activities, this year’s winter lockdowns alone may have reduced Australia’s GDP by $17bn between June and August.[7]

Luckily the federal government has supported those affected by the policies. But as of May 2021, the federal government had spent $291 billion on pandemic-related economic support, a number that will increase with every day our country remains in lockdown.

These are enormous sums, so our COVID-Zero policies raise an obvious question for us: can we afford to keep locking down our economy?

Businesses and working people have suffered immense damage during the pandemic so far. Our COVID-Zero policies severely constrain the hours worked in our economy. After falling dramatically during the early days of the quarantines, quarterly hours worked—a statistic that tells us how much work employed people do in our country every three months—only just returned to its pre-pandemic level in June 2021. With the new lockdowns, we ought to expect them to fall once again.

Furthermore the cost of the lockdowns isn’t distributed evenly through the economy. Low-income service, tourist and retails workers see the greatest risk to their livelihoods during lockdowns,[8] while younger people with more years left to live will bear most of the consequences of policies that protect the elderly more than anyone else. The fall in employment is also concentrated in the private sector. Between June 2019 and June 2020, the private sector shed 541,700 of its roughly 11,000,000 employees while the public sector lost only 5,500 of its 2,000,000 workers. This decline brought the share of total employment made up by public sector workers in Australia from 15.9% to 16.6%; at the same time, the public sector wage bill rose by 4% while the average wage grew by just 1.4%.[9]

This inequality extends to businesses too. Some economists fear the lockdowns will transform the economy’s structure, shifting us away from small businesses and towards international conglomerates. [10] The rationale for their anxiety is sound: during lockdown, consumption declines, small business retail sales plummet and people shift towards online shopping with large businesses like Amazon.[11] Data on the number of Australia small is only available up to the 2018-19 financial year, but it is likely that the COVID lockdowns will exacerbate a trend observable since 2014-15: the share of people working for big business will increase at the expense of the share employed by small businesses.[12] Complicating this however are some surprising stats: after a predictably bad year in 2019-20, the net increase in the number of businesses was 45% higher in 2020-21 than in 2018-19.[13] Many of these will be small businesses so we must wait to see how this surge in business creation affects the economy.

Beyond economics, the lockdowns have also had significant health effects of their own; the cost to our brains is particularly shocking. Recent research suggests that lockdowns have starved American children of social interaction, leading to a fall in average IQ of 22 points of those born during the pandemic.[14] Neuroscientists also worry about the effects of boredom, isolation, stress and inactivity upon adults, many of whom report experiences of cognitive decline and memory loss during lockdowns.[15] And a paper by the USA’s National Bureau of Economic Research also suggests the unemployment shock caused by the COVID lockdowns has likely increased mortality rates and reduced life expectancy.[16] The NBER researchers forecast nearly a million extra deaths in the US over the next 15 years from lockdown’s unemployment effects alone.

Scientists have also recorded a surge in cases of depression and related mental health problems: partly owing to the lockdowns, a psychological ‘shadow-pandemic’ has accompanied the virus’s spread as people worldwide.[17] In the USA, the share of people experiencing anxiety and depression was at 41% in January 2021, a nearly fourfold increase from the same month in 2019.[18] On a more personal level, a British friend told me the UK lockdowns robbed her of a year of her life. Her mournful sentiments reflect those of others I know, who must now find a way to understand and replace the futures they have lost because of our policy choices.

We should be worried about these health concerns, not least because they carry significant economic costs of their own. Yet we mustn’t discount COVID-Zero’s social and economic benefits. Research from the Lowy Institute places us in the top 10 countries worldwide for our medical response to COVID. It’s easy to see why they did so:[19] relative to other countries Australia has an incredibly low COVID per capita death count – 38.38 deaths per million people. Currently we have had less than 1,000 COVID deaths: had we experienced the UK death rate of 1960.89 per million, 49,000 Australians would have died of COVID. Our excess mortality rate has also been lower than the UK and the US for almost the entire pandemic.[20] Though the government’s lockdown policy has significantly constrained our liberty, so far they have protected Australians against the worst human costs of the pandemic. For that we should be grateful.

Humanistic benefits aside, University of Melbourne research also shows that ‘very hard, very early’ lockdowns may be better for health, life and the economy in the long run.[21] Hard and early lockdowns cause severe economic harm in the short run. Yet they eventually lead to fewer days spent in lockdown and a lower death count, giving countries an overall economic benefit.[22] Plenty of other research reports similar findings: a professor at the Australian National University has argued that stronger COVID suppression policies lead to fewer deaths and less damage to GDP per capita. The argument that we can choose to contain COVID or save the economy, he says, is a false dichotomy.[23] Australia’s Treasury department seems to agree with the university researchers. They say the COVID-zero approach is ‘more cost effective than allowing higher levels of community transmission, which ultimately requires longer and more costly lockdowns.’[24]

IMF data further supports the idea that saving lives is compatible with protecting the economy. Australia had a lower per capita death rate and a smaller percent decline in GDP in 2020 than the UK, the US, Canada, France, Germany and Denmark. We even bested Sweden on both measures – a country that imposed no lockdowns whatsoever.[25]

Most importantly, if we add up the value of increased government spending, lost revenue, and the amount of equity, loans and guarantees provided in each country, Australia spent more in 2020 than only eight other developed countries analysed by the IMF.[26] Our approach has been cheaper and better than many others’.

While we should be cautious about offering conclusions before the pandemic is over, it seems that Australia has done relatively well so far. Of course, we shouldn’t take full credit for our success, nor should other countries like Sweden blame themselves entirely for their failures: in our globalised economies, our recovery depends largely on the actions and successes of our trading partners. Just like the recovery from 2008’s crash, China is partly responsible for our economic health. The value of our exports surged during the crisis, rising by about 33% between August 2020 and August 2021;[27] this was partly driven by the Chinese government’s construction-oriented economic stimulus that drove up the price of iron ore.[28] China’s policies have been good for Australia in some ways. Yet with Chinese demand falling, the price of iron crashing, and our continued lockdowns in the southeast, our economic success may dwindle over the coming months.

The political implications of our success are also serious. The Lowy Institute’s research mentioned before says authoritarian countries had the greatest success in handling the pandemic. Australia is supposed to be a liberal democracy, but our government undemocratically suspended our freedom for months in the pandemic. While Sweden’s liberal approach has ultimately left them in a far worse position than us,[29] our federal and state governments were highly authoritarian during the pandemic; the latest symptom of this is the police suppression of lockdown protests.[30] Without consulting the population, they decided at the pandemic’s start that survival was more important than freedom, even if it came at a great personal cost. They said life trumped liberty. I’ll let the reader think about what this means.

Political concerns aside, if our goal is to save lives while protecting our economy, the story of 2020 seems pretty unequivocal: COVID-Zero was not only better for our health; it was also better for business.

II. The Future of COVID-Zero (or, What Happened to ‘Flattening the Curve’?)

Australia has fared better than other countries both medically and economically. Fewer lives have been lost to COVID, our government has spent less and our GDP is in better shape. It seems that our COVID-Zero policy is responsible for our success.

But some questions remain: when and why did we decide to aim for ‘no community transmission’? Weren’t we supposed to ‘flatten the curve’ and go into lockdown for only a few months?

Those unaffected by lockdown-induced memory loss might recall that COVID-Zero was not our nation’s original strategy. In March 2020, we rejected both New Zealand’s ‘eradication’ approach and Sweden’s decision to let the virus run free. Instead our government first tried to contain and control the virus’s spread: they chose to ‘flatten the curve’, prolonging the pandemic while making it less severe.

On April 17th last year the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) explained the strategy’s purpose. Flattening the curve means reducing the ‘rate of epidemic growth’ to a manageable level. To do so, the government would use temporary lockdowns, masks, and social distancing to make sure the medical sector wasn’t overwhelmed and give them time to build their capacity to treat the seriously unwell.

In the pandemic’s early stage, there was widespread support for ‘flattening the curve.’ People often compared it positively against New Zealand’s hard ‘eradication’ approach.[31] You might even recall Scott Morrison telling us to ‘flatten the curve’ throughout April, then triumphantly claiming that ‘we have flattened the curve’ in May.[32]

For a couple of months, Australia flattened its curve: we saw a constant and small trickle of new cases. Yet soon after Morrison spoke, Melbourne entered its second lockdown, and our national strategy quietly changed. On July 24th, Scott Morrison and the AHPPC introduced the COVID-Zero approach in two separate press releases, where they said that our goal was no longer to flatten the curve but to ensure there was ‘no community transmission’ of the virus.

Public health specialists have the eradication approach over ‘flattening the curve’ since the pandemic’s start;[33] some have even endorsed it. Yet when we changed our policy, neither Morrison nor the AHPPC explained why the shift was necessary.[34] The AHPPC even doctored history a little in their release, saying that ‘no community transmission’ was their goal ‘from the start of the pandemic,’ even though their first public use of that phrase in the context of COVID strategy occurred on July 24th.[35] As they stated on March 17th, their strategy beforehand was to keep the epidemic growth rate below one:[36] only in a pedantic sense is this the same goal as zero transmission.

The lack of explanation for the change to COVID-Zero is disturbing, even if later evidence largely vindicates the government’s choice. But whether COVID-Zero was the better policy, recent developments have opened a new pathway for us.

The COVID-Zero policy successfully minimised community transmission for about nine months. Between September 2020 and June 2021, daily new case counts remained in the low-double digits. Yet with the latest outbreaks in the southeast states, Australia is now on track to break 1000 cases a day. With this soaring case count, it would be incredibly difficult—and not to mention costly—to return to a point where we record only a few new cases a day. Morrison himself has said it’s ‘highly unlikely’ we would do so.[37] The days of COVID-Zero may now be a thing of the past.

Yet there is a new alternative: Australia will soon have enough vaccines to inoculate the population against COVID-19. Relying on modelling from the Doherty Institute,[38] Morrison now says lockdowns ‘won’t be necessary for much longer.’ Once they vaccinate 80% of the population, the government will impose only ‘highly targeted’ restrictions on the Australian people.[39] At the moment, it isn’t exactly clear when exactly when we will reach the required vaccination level.[40] There are even murmurings among the state governments about whether they will refrain from lockdowns once we achieve this target;[41] Berejikilian recently said some restrictions will remain in place even after NSW reaches the 80% vaccination target.[42] But now safe and effective vaccines are available, it seems like the end of the lockdowns is in sight. For once we are vaccinated and hospitalisation rates have fallen, the public health justification for lockdowns will be no more.

Despite this glimmer of hope, it isn’t clear that Morrison will be able to uphold his promise. Things remain highly uncertain. Currently, scientists worry about the emergence of a vaccine-resistant variant of COVID-19, and the Pfizer CEO has said one is likely to emerge eventually.[43] The Delta strain of COVID is already more resistant to vaccines compared to the original and Alpha variants.[44] Recent research also says that Delta’s viral load is up to 300 times greater than the original strain, while vaccinated people can carry a similar viral load to the unvaccinated.[45] Vaccines, it seems, do not stop the spread of Delta; instead, they reduce its harm to individuals. More worryingly, the newer Lambda variant—one of at least five other COVID strains you may not know about—might be even more vaccine-resistant.[46] The Lambda variant has followed the Delta variant to Australia, and it may only be a matter of time until the virus overwhelms us again and the government starts imposing lockdowns once more.

In the first year of the pandemic, it seems that COVID-Zero was the right policy. But if the pandemic continues and lockdowns remain necessary even after we are vaccinated, can we afford to return to COVID-Zero? The policy is enormously expensive and people are tired of the interruptions to their lives. Despite this, the short-run evidence suggests we really can’t afford to do anything else: as we saw COVID-Zero leads to better outcomes for our health and economy.

Yet the question is far more complicated than most of our politicians and scientists are prepared to admit, for we ultimately have no idea what our political decisions today will bring in the long term. The virus inflicts death and suffering and while the lockdowns mitigate its mindless violence, they cause losses of their own. Both are a source of grief and as Ellen Cushing wrote in The Atlantic, ‘we simply don’t know the long-term effects of collective, sustained grief.’[47] The long-term economic, political and psychological effects of the COVID-19 crisis and our response to it are unknowable today. The passage of history and grief and loss is completely unpredictable. The best we can do is to act with moderation and caution while constantly re-evaluating our approach. It seems like we have moved in the right direction so far, and in the absence of other ideas, arguably we should continue. But only time will reveal whether our COVID-Zero policies were worth it. Let’s hope they are.

REFERENCES

[1] See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-58277503

[2] See https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/14/lockdown-fines-raised-as-australia-faces-worst-covid-situation and https://www.stuff.co.nz/world/australia/126071729/covid19-in-australia-415-new-cases-as-diabolical-delta-strain-continues-to-spread-in-nsw

[3] See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/aug/23/nsw-covid-19-lockdown-restrictions-sydney-suburbs-regional-new-south-wales-lgas-act-canberra-update-coronavirus-face-mask-rules-explained-5km-radius-travel-masks

[4] See https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2021-07-21/australia-s-covid-zero-strategy-hits-a-wall and https://edition.cnn.com/2021/08/22/australia/australia-morrison-zero-covid-19-borders-intl-hnk/index.html

[5] See https://www.health.gov.au/news/eliminating-covid-19-a-false-hope

[6] See https://www.pm.gov.au/media/update-coronavirus-measures-160420

[7] See https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/cost-of-lockdowns-is-17-billion-and-counting-20210812-p58i58.html and https://theconversation.com/yes-lockdowns-are-costly-but-the-alternatives-are-worse-163572 and https://www.couriermail.com.au/business/qld-business/bloody-furious-lockdown-anger-as-economy-takes-700m-hit/news-story/96532c6a20084944621f73e3852616da and https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/off-a-cliff-qld-businesses-pay-multimillion-dollar-toll-for-lockdown-20210630-p585la.html and https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/capital-lockdowns-to-deliver-2-5b-hit-as-business-takes-another-blow-20210629-p5859c.html

[8] See https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00241/full

[9] See https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/annual-wage-growth-remains-14 and https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/jun-2020 and https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/employment-and-earnings-public-sector-australia/latest-release and https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/jun-2020

[10] See https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/07/09/after-covid-19-giant-corporations-chains-may-be-only-ones-left/

[11] See https://www.smartcompany.com.au/finance/economy/lockdowns-small-business-owners-pandemic-jason-murphy/

[12] See p.10 of https://www.asbfeo.gov.au/sites/default/files/ASBFEO%20Small%20Business%20Counts%20Dec%202020%20v2.pdf

[13] See https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/business-indicators/counts-australian-businesses-including-entries-and-exits/latest-release

[14] See https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/12/children-born-during-pandemic-have-lower-iqs-us-study-finds

[15] See https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/03/what-pandemic-doing-our-brains/618221/ and https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jun/24/pandemic-brain-covid-coronavirus-fog-concentrate

[16] See https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28304/w28304.pdf

[17] See https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/health/2021/03/mourning-and-melancholia-psychological-shadow-pandemic and https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00175-z

[18] See https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

[19] See https://interactives.lowyinstitute.org/features/covid-performance/#politics

[20] See https://ourworldindata.org/excess-mortality-covid

[21] See https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/we-need-to-talk-about-elimination-vs-suppression-in-australia-again

[22] See https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2021/number/1/article/covid-19-lockdowns-fatality-rates-and-gdp-growth.html

[23] See https://theconversation.com/data-from-45-countries-show-containing-covid-vs-saving-the-economy-is-a-false-dichotomy-150533

[24] See https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-08/PDF_Economic_Impacts_COVID-19_Response_196731.pdf

[25] See https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104709/coronavirus-deaths-worldwide-per-million-inhabitants/ and https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

[26] See https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19

[27] See https://tradingeconomics.com/australia/exports

[28] See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-23/iron-ore-crash-economy-dollar-analysis/100396988

[29] See https://www.businessinsider.com.au/sweden-covid-no-lockdown-strategy-failed-higher-death-rate-2021-8

[30] See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/aug/21/australia-anti-lockdown-rallies-protesters-violently-clash-with-police-in-melbourne

[31] See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-27/coronavirus-options-to-end-lockdown-explained/12090270

[32] See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-23/how-scott-morrison-language-changed-coronavirus-pandemic-year-on/13075506

[33] See https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-maths-and-ethics-of-minimising-covid-19-deaths and https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-27/coronavirus-options-to-end-lockdown-explained/12090270

[34] See https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-statement-on-strategic-direction and https://www.pm.gov.au/media/national-cabinet-24jul20

[35] See https://bit.ly/3BcovQJ

[36] See https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-coronavirus-covid-19-statement-on-17-march-2020-0

[37] See https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/coronavirus/scott-morrison-says-australia-highly-unlikely-to-reach-covid-zero-again-ng-b881977188z

[38] See https://www.doherty.edu.au/uploads/content_doc/DohertyModelling_NationalPlan_and_Addendum_20210810.pdf

[39] See https://www.news.com.au/national/politics/pm-scott-morrison-says-covid19-focus-needs-to-change-from-cases-to-hospitalisations/news-story/3dc575ff7774e5a3b33bc5def6a9191e

[40] See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jul/30/australians-will-be-able-to-freely-travel-overseas-when-80-of-the-population-is-vaccinated-morrison-says

[41] See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/aug/20/scott-morrison-warns-leaders-not-to-break-covid-reopening-deal-ahead-of-national-cabinet-meeting

[42] See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-17/nsw-covid-19-restrictions-to-remain-after-vaccination-high/100381078

[43] See https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/15/new-covid-variants-will-set-us-back-a-year-experts-warn-uk-government and https://www.insider.com/pfizer-ceo-vaccine-resistant-coronavius-variant-likely-2021-8

[44] See https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01696-3

[45] See https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/delta-variant-cases-show-300-times-higher-viral-load-shows-south-korea-study-2517757 and https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/19/jabbed-adults-infected-with-delta-can-match-virus-levels-of-unvaccinated

[46] See https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ and https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/lambda-variant-of-covid-19-might-be-resistant-to-vaccines and https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/delta-infections-among-vaccinated-likely-contagious-lambda-variant-shows-vaccine-2021-08-02/ and https://theconversation.com/covid-lambda-variant-is-now-in-29-countries-but-what-evidence-do-we-have-that-its-more-dangerous-163936

Economics After COVID: Boom, Bust, or Something In-Between?

By Alasdair Cannon

Executive Summary

- In 2021, we hope that the end of the pandemic will come. But what will our post-pandemic economies look like? A few scenarios are possible.

- Boom: Some believe that savings accumulated during 2020’s lockdown will fuel a boom, as pent-up demand is unleashed on the economy.

- Bust: But there is also a chance of a debt-crisis once loan moratoriums end.

- Politics: Long-term recovery depends on our politics – we must change the policies that led to a low-growth, low-investment environment even before the pandemic.

- If business and government take the right actions now, there is reason to hope for a better future.

I. After the Pandemic…

In March 2021, the pandemic’s end seems tantalisingly close. An unprecedented vaccine was created with miraculous speed, and now governments worldwide are inoculating their populations against the COVID-19 virus. With continued fortune and perseverance, lockdowns and quarantines will soon be a thing of the past, along with their economically disastrous restrictions on human freedom.

This is good news. Nonetheless, it isn’t clear what kind of world we will return to once we can freely leave our homes again. Economists like Joseph Stiglitz fret over the ‘long-term scarring’ our economies have suffered during lockdown. His worries are justified: most signs point towards an almost inconceivable level of damage whose long-term effects are obscure. In 2020, the UK suffered its worst recession in over 300 years. The UK’s GDP fell by 9.9% last year, a fall whose magnitude is unmatched in any crisis since the Great Frost of 1709, a winter so cold that waterways and trade routes froze, and tree trunks shattered where they stood.[i] COVID-19 gave the world and the UK a dark winter, the true consequences of which won’t be understood for years to come.

Elsewhere, though, there are signs that an economic boom may occur once the virus is controlled. Some people argue that the savings accumulated during the pandemic could be converted into a rush of economic activity that will stimulate the economy back into prosperity. There is weight to this hypothesis: a large surge in consumer demand caused a ‘global supply chain crunch’[ii] in February this year, forcing Australian exporters to scramble for scarce shipping containers.

As the vaccine is administered, we hope for the recovery of our health and our economies. Despite our hopes, the future remains ambiguous. Recovery, depression, stagnation – we simply don’t know what we’ll face once we contain the virus. Of course, we cannot eliminate this ambiguity any more than we can see the future before it arrives. But we can try to understand it. Doing so is imperative if we want to coordinate our economic activities over the coming months and years. Thus, we must try to grasp the opportunities and threats that could arise in our post-COVID world while considering how these can be turned into long-term gains. Such is the only way towards a reasonable hope, after all.

II. Boom: Pent-Up Demand

Recently, commentators have proposed a scenario that could lead to a hopeful future after COVID-19: the release of consumers’ ‘pent-up demand’. The New York Times ran an article on February 21st that epitomised this notion, entitled ‘On the Post-Pandemic Horizon, Could That Be… a Boom?’[iii] There, the Times argued that an economic boom could occur when lockdown ends, as people spend the ‘trillion-dollar mound of cash’ accumulated during quarantine as a ‘result of lockdown-induced saving and successive rounds of stimulus payments’. They hope that money unspent last year will be spent this year, that 2020’s ‘pent-up demand’ will be unleashed in 2021, causing a ‘supercharged’ economic recovery and ‘years of stronger growth’.

Not often discussed, ‘pent-up’ demand is a simple and intuitive concept. During a lockdown, people are unable to spend their money in the ways they ordinarily would. They are also deprived of outlets for their usual consumer desires. Unable to travel, eat at restaurants, or visit cinemas, people who keep their jobs save money at an above-normal rate, while their desire for various goods and services becomes ‘pent up’.

A lockdown thereby creates a unique situation: repressed consumer wishes are combined with an abundance of cash. So, when the lockdown is lifted and people embrace their restored freedom, they rush back into the economy, spending their excess savings on the pleasures they missed. The demand ‘pent-up’ during lockdown is thus unleashed on the economy. Consumption spending, business activity and economic growth suddenly increase.

There are historical precedents for this kind of consumer behaviour. NPR’s Planet Money recently described how attendance at American baseball games plummeted in 1918, as the Spanish Flu broke out towards the end of WWI. When the war ended, and the pandemic had mostly cleared, attendance skyrocketed. 6,532,439 people went to a baseball game in 1919, more than double the number for 1918.[iv] This dynamic from the end of the 1910s is exactly what people forecast for the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, where US savings rates reached an all-time high of almost 26%.[v]

As the shortage of shipping containers mentioned before shows, pent-up demand is being released right now. While shortages are undesirable and can cause price inflation, we can rightly read this as a sign of recovery. Though it is too early to determine its extent, a revival of economic activity is underway as consumers spend their accumulated savings.

With pent-up demand, new opportunities for prosperity are therefore emerging right now. This is a cause for optimism: however, we must temper our fledgling hope with a few caveats.

First, we can’t expect that all of 2020’s deferred demand will become spending in 2021. In all likelihood, some fraction of 2020’s demand has been irrevocably lost. Time has passed and wants have waned. Compounding this is the natural hesitation that descends on an economy after a crisis. There are so many uncertainties at the moment – How effective are the vaccines? Will the virus mutate? Will we return to lockdown? Is another crisis coming? – that people will probably save this money to insure against future adversities.

Beyond this, we must remember that the direct gains from pent-up demand may only be temporary. At most, people will be able to spend a small portion of a year’s income in their post-lockdown rush. There is also no reason that the release of pent-up demand will cause a permanent increase in rates of consumption spending. If anything, people are likely to remain more conservative than before due to the prevailing economic uncertainty and will reduce their spending once their pent-up demand is exhausted.

Allowing the gains from pent-up demand to vanish in this way would be a waste. But if we want the gains to be permanent, pent-up demand must be directed towards the right ends. Funnelled towards industries and projects where profitable, long-term investment opportunities exist, the eruption of post-pandemic demand will support these investments and the jobs they create.

Pent-up demand is not a panacea for the COVID crisis, but it is an opportunity. Used properly, it could be a platform for long-term prosperity, growth and recovery. Spent on short-term opportunities, the macroeconomic improvements will be similarly short-lived. Policymakers and business leaders should act appropriately to ensure a slow-burn over a flash in the pan, as only the former will restore us to prosperity.

III Bust: Debt Crisis?

Against the opportunities implied by pent-up demand is the looming threat of a debt crisis.

In a remarkable moment in the pandemic’s early days, governments worldwide declared moratoriums and forbearances on debt repayments. Australians and Americans, among others, were relieved of their obligations to various debts, like mortgages and student loans, while landlords were banned from evicting their tenants in both countries. Of course, this protected the vulnerable from the ravages of a conjoined health and economic crisis. But these measures also contributed to the high saving rates observed during lockdown, and allowed income to be repurposed for consumption spending, helping stimulate the economy.

The moratoriums were an admirable and necessary action. However, they were always destined to be temporary. In Australia, many of these protections have already ended. Moratoriums on evictions remain only in South Australia and Victoria but will conclude in March 2021,[vi] and debt repayment provisions expired last year. And Americans will gradually lose their protections between March and September 2021.[vii]

Soon, banks will demand payments from their customers once more. Depending on the state of the economy – especially whether the indebted have returned to work and/or have enough savings to cover their loan commitments – this demand could quickly become catastrophic. If people in indebted households are still unable to work, restarting debt obligations will strain their savings. Aside from dampening their ability to stimulate the economy and unleash their pent-up demand, it could force them into insolvency and vagrancy. If enough people are pushed to this extreme, aggregate demand will fall while banks will be hit with large losses. End the moratoriums too soon, then, and we could provoke a debt crisis and an economic recession at once.

It is impossible to say whether a catastrophe like this will occur in 2021. However, the data suggest a growing vulnerability. In the USA, mortgage delinquency rates across all loan types increased substantially through 2020.[viii] Meanwhile, total US household debt reached an all-time high of $14.6tn by the end of last year.[ix] In Australia, the household debt-to-income ratio remains historically high.[x] And in both countries, the unemployment and underemployment rates are still elevated. While these variables aren’t conclusive, the government must be careful when revoking these measures. We do not need to add a financial crisis to our existing problems.

IV The Long-Term: An Opportunity to Improve?

Pent-up demand and the possible debt crisis are short-term issues: they will probably come to a head within the next year or two. Of equal or greater importance, however, are the longer-term systemic issues that the COVID crisis has brought to light. Like those already discussed, these also present causes for optimism and caution.

Nobody would deny that COVID-19 has brought destruction to economies around the world. Our human capital stock has been damaged through death and educational disruption, and the long-term effects of this will be significant. Nonetheless, like a cleansing fire, COVID-19 has also cleared the way for growth and improvements in our economies. Many businesses have closed, but we have gained the space to create new and better businesses in their place. And when we started working from home during lockdown, we improved workplace communications technology and discarded inefficient and outmoded norms about our workplaces. The need to commute to work has been eliminated for people worldwide, reducing noise, traffic, and pollution in our cities, while freeing up more time for productive work and leisure for workers. Make no mistake: this is a significant economic transformation that will reshape our societies for years to come.

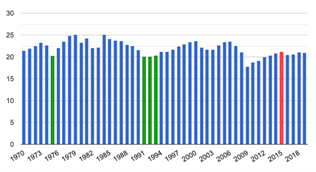

The COVID-19 crisis also presents an impetus and opportunity for reforming our wider economic paradigm. Advanced economies around the world were not thriving before COVID arrived. As the World Bank reports, the ‘global economy headed into the COVID-19 pandemic on the heels of a decade of slowing productivity growth and weak investment.’ Their research found that by 2018, labour productivity growth in advanced economies had slowed to 0.8% from 1.0% between 2000-09. And in 2019, investment growth had fallen below its 2000-09 average in two-thirds of the world’s economies.[xi] The situation in the USA is particularly unimpressive. Despite talks of a ‘strong economy’ in recent years, the best year for capital investment after the GFC was worse than all but four years between 1970 and 2008 (See Chart 1).

Around the world, there is a problem with investment. Yet it was not caused by an insufficient level of savings or liquidity but an unwillingness to invest. Before COVID-19, confidence in real economic investment had evaporated. This should be no surprise, for the COVID crisis is our third major economic downturn since the year 2000. It was also a threat that was predictable and possibly preventable but which nonetheless caught our governments off-guard, causing dramatic variations in responses from country to country. Business investment cannot thrive where instability prevails. Capitalism has decelerated and stagnated in recent years because our economic systems have become startlingly fragile and vulnerable.

Crucially, the repeated collapses and overall economic slowdown are not anomalies: they are signs of structural weaknesses. The neoliberal reliance on deregulated markets and our successive rounds of financial market support through bailouts and quantitative easing has led to a toxic situation: repeated crises have destroyed business confidence and forced interest rates to their all-time low, while financial markets have boomed due to government interventions. Thus, it has become rational for people to substitute away from real economic investment towards investment in shares: the returns to shares are larger and more secure.

The consequence of this, however, is an acceleration of share market growth coupled with a slowdown in real economic growth, which worsens with every new crisis, bailout and rate cut. This situation prevails in the US today. Between 2010 and 2020, nominal US GDP increased by roughly 40%,[xii] while the S&P500 index increased by nearly 200%. Stocks or the real economy: as an investor, where would you have put your money? Between the GFC and the COVID-19 crisis, the rational investor would have chosen stocks.

If we want our societies to recover and thrive after the COVID crisis – that is, if we want to rebuild our economies so they have higher GDP growth, more jobs, and better wages – we must commit to a course of action that supports real business investment and aggregate demand. We must use this as an opportunity to improve. Thus, we should support business investment in profitable projects that grow the real economy. These will create jobs, further supporting incomes, aggregate demand and continued investment in the future. Incentives for people to shift money from financial markets into the real economy are also necessary. At present, too much capital is tied up in non-productive investment: if we want a strong recovery, this money must enter the real economy. Likewise, if we support aggregate demand, businesses are more likely to invest because they can rationally expect greater profitability. To this end, policies to ensure that recovery is spread across high-income and low-income households are necessary, as are policies that encourage spending and stimulus throughout the economy.

Chart 1: USA Capital Investment as % of GDP, 1970 – 2019.

Source: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/usa/capital_investment/

V On The Brink of the Future

Today, as always, we stand on the brink of the future. But our view is not clear. In the post-COVID world, the chance for prosperity mingles with the threat of new disasters. Tomorrow, we could have a vital and booming economy, or we could face stagnation or deep depression.

What happens next depends on our political and economic decisions. But it will also be shaped our attitudes toward the future. If we want our economic possibilities to be more hopeful, a collective optimism must prevail between businesses, individuals and governments today. The investments and actions needed for long-term prosperity will not otherwise occur. In pessimism, however, our future will necessarily become bleaker.

Against the catastrophe of 2020, a realistic and hopeful perspective is as necessary as pragmatic and efficient actions. At all levels, we must make efforts to foster a legitimate hope. Informed, optimistic beliefs will direct our actions towards the better future that we, those in the wake of disaster, so desperately crave. Our task, then, begins by understanding our situation, and all the risks and opportunities of our transformed world. It ends with effective, productive actions and a hopeful perspective: with views and decisions that reinforce one another for the better.

Endnotes

[i] See https://www.barrons.com/articles/u-k-is-headed-for-worst-recession-since-great-frost-of-1709-51588884310

[ii] See https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2021-02-01/food-shipping-container-shortage-puts-squeeze-on-trade/13100728

[iii] See https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/21/business/economy/pandemic-economic-boom.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage

[iv] See https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2021/01/12/955617983/what-1919-teaches-us-about-pent-up-demand

[v] See Joseph Stiglitz’s report, ‘The Economy of Tomorrow: Recovering and Restructuring After COVID-19’ at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/RI_-RecoveringandStructuringAfterCOVID19_IssueBrief_202010.pdf

[vi] See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/nov/25/australias-rent-bomb-risk-means-countless-renters-could-face-eviction and https://ndh.org.au/debt-problems/housing/covid-19-changes-home-loans/

[vii] See https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/20/biden-to-extend-the-national-ban-on-evictions-through-march-2021.html; https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/02/16/fact-sheet-biden-administration-announces-extension-of-covid-19-forbearance-and-foreclosure-protections-for-homeowners/; and https://studentaid.gov/announcements-events/coronavirus

[viii] See https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc

[ix] See https://www.statista.com/chart/19955/household-debt-balance-in-the-united-states/

[x] See https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/household-sector.html

[xi] See p.115 of their January 2021 ‘Global Economic Prospects’ report.

[xii] Real GDP increased by approximately 18% over the same period. Stats are sourced from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ National Data. See https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Voodoo Finance For Sick Markets: Stock Prices During COVID-19

By A. F. Cannon

Writing for Real Time CEO

Today, finance and economics have nothing to do with one another. I deliberately open with this ridiculous statement because financial markets in the last year have behaved in ridiculous ways. In 2020, the real economy in the USA shrank significantly; yet financial markets boomed. Some commentators have said that these trends defy logic and reality; others see how it mirrors the history of markets after the GFC. Either could be right; all we know, however, is that we need to understand it ASAP.

(I) Crash!

We’ll start with a brief history of our present situation – the COVID-19 lockdowns that have wrought economic havoc around the world.

In February, the World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, and economies around the world moved into an unprecedented lockdown. A massive shock rippled through the world’s markets as whole industries were pushed to the brink of ruin.

In response, respectable institutions began to issue dire GDP growth predictions. By March, Deutsche Bank said US GDP would fall by 12.9% in Q2 of 2020,[i] the largest quarterly fall since WWII. Goldman Sachs was even more pessimistic, predicting a contraction of 24% – an amount 2.5 times greater than anything in US history.[ii] Both were wrong. GDP instead contracted by 31.4% compared to Q1 2020 – a period where economic activity already fell 5% compared to Q4 of 2019.[iii]

Thus the US economy entered a dismal retraction, and financial markets responded accordingly. By mid-March, the S&P500 had fallen 30% from its historic highs, from 3379.45 pts on February 10th to 2237.40 pts on March 23rd. The signs were clear: 2020 was going to be a terrible year for investors.

But then, something remarkable happened. After the S&P500 hit its nadir in late March, it began a steep ascent, reclaiming 1000 points before June 30th. The New York securities industry doubled their usual first-half profits, taking home $27.6 billion before July.[iv] And on September 9th, the S&P500 reached its all-time high – 3580.84 pts. Investors rejoiced – somehow, despite the crisis, capital gains had increased.

Despite the dismal outlook, the S&P500 boomed in 2020. Share prices rocketed upwards, even while the real economy suffered incredible losses. So, I’ll reiterate: today, finance and economics have nothing to do with one another. Indeed, it seems like we’ve entered a system of what Joseph Stiglitz has called ‘ersatz capitalism’ – a land where share prices are divorced from real profits, and where markets behave like pale imitations of themselves.[v] Even our markets, it seems, have fallen victim to ‘post-truth’ politics.

(II) “It Makes No Sense”

Faced with these facts, a good friend of mine proclaimed that these movements contradict the logic that supposedly governs our economies. In his words: “It makes no sense.”

Like most others, he thought a) share prices should increase with demand, and b) demand for a firm’s shares goes up when we expect the firm to make more profit. He believed that prices are ‘rationally determined’ by a justified belief in future profitability.

To his credit, reality usually abides by this thinking: indeed, it is exactly why the stock market plummeted between February and March last year. People expected profits to fall, so prices declined.

But after the collapse in March, markets started contradicting these assumptions. Prices climbed even as the economy contracted. The demand for shares increased massively following the COVID-19 shock – even though the outlook for profitability and economic growth was dire.

If we believe share prices should depend on our expectations of profit, then we have to say: “It makes no sense.” And yet this our world today: we live in a time where economic reality no longer reflects the average person’s idea of economic theory.

(III) Making Sense, pt. I: Keynes

For this reason, we need a better theory. We must continue to make sense, even where reality starts to look unreal.

Luckily for us, a better theory already exists. All we need to do is abandon our idea that share prices are determined by considered, rational expectations of future profits. Instead – with thinkers like Keynes and Minsky – we must learn how irrationality rules markets, and how government intervention can distort prices.

To rehabilitate our ideas, we’ll turn first to one of the most important pieces of economic writing ever produced: Chapter 12 of Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money. In this short and brilliant essay from 1936, Keynes reveals the irrational behaviours that emerge when humans face an unknowable future. He has a particular interest in the unjustified conventions, beliefs and emotions we use to guide our decisions – that is, the human habits that make a mockery of our rationalistic pretensions.

Conventions

Keynes begins by discussing humanity’s tendency to rely on conventions for thinking when faced with uncertainty. As a trader himself, Keynes knew that humans have a habit of valuing stocks by assuming that the existing state of affairs will continue to prevail in the future.[vi] While this is irrational, the future is inherently uncertain; thus we have no alternative. Without a specific reason to do otherwise, we will usually believe that tomorrow will be like today.[vii]

Beliefs

Compounding this problem, Keynes also saw that accurate forecasts of profitability don’t fully determine share prices. Indeed, these forecasts are often irrelevant to investors, who spend their time trying to pre-empt what ‘average opinion expects the average opinion [of a stock’s value] to be’.[viii] The demand for shares changes based on fluctuations in investors’ beliefs about other investors’ beliefs. For an investor, it’s often more important to correctly guess the market’s belief about what will happen to a stock’s value than to accurately estimate future profitability – irrespective of whether those beliefs are informed or rational. Being right about profitability is not the same as actually making profits.

Emotions

Lastly, Keynes also saw how our investment decisions can be based on non-rational, emotional forces. He rightly states that our decisions affecting the future ‘cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation, since the basis for making such calculations does not exist’. That is, because we can’t see the future, we lack the ability to rationally calculate expected profits. Without the security of mathematics, we instead rely on ‘whim or sentiment or chance’ to make our choices. Thus, our markets are comprised of millions of people, buying and selling shares based on changes in their ‘spontaneous optimism’ rather than rational, knowledgeable calculation.[ix] Markets are driven by the heart – not the mind.

Implications

The truth about a firm’s future profitability can be irrelevant to share price. Our irrational taste for convention, belief and sentiment ensures that neither rationality nor logic determines share prices. Prices are irascible and maddening – much like the humans who try to control them. Accordingly, we must account for ‘the concealed factors of utter doubt, precariousness, hope and fear’ at play in our markets.[x] Failing to do so will leave us entirely blind about the truth of prices.

(IV) Making Sense, pt. II: Minsky

From Keynes, we learn that prices are not determined by rational laws, but by emotion and belief. Prices behave irrationally; rational expectations have never prevailed. We must accept this as the first truth of our markets; doing so will allow us to move towards an understanding of the erratic behaviour of markets in 2020.

However, Keynes’ thoughts don’t fully explain our situation, where share prices rose even though we knew profitability would fall. Our society seems to have gone beyond irrationality into a collective defiance of economic theory altogether. At this point, it looks like we are more anti-rational than irrational.

To understand our anti-rational markets, we must go beyond Keynes, and try to understand the role of government intervention. As we will see, the government has the power to sculpt the future by fixing expectations. They can move us from irrationality into anti-rationality because they can make us believe that shares will be profitable – even if we know this should be impossible.

The Financial Instability Hypothesis

Here, we turn to one of Keynes’ successors: Hyman Minsky. Like Keynes, Minsky was concerned with the surges and retreats of ‘spontaneous optimism’ that dominate the financial markets. But Minsky went a step further than Keynes: he saw how the mechanisms of the financial system could lead this optimism to snowball into ‘an explosive euphoria’.[xi] He saw how euphoria could cause the economy to collapse into a heap of insolvencies. And he saw how the government, faced with financial collapse, could permanently distort market outcomes.

His theory – the ‘financial instability hypothesis’ – is complex and elegant. To put it simply, it says that booming economic conditions lead banks to loan money in increasingly risky ways. Essentially, the banker’s confidence improves with the economy. As GDP grows, his faith in the ability to profit from his loans also increases. The banker takes greater risks, meaning that debt repayments become more precarious as the economy booms. So, when a shock inevitably hits, and people are unable to meet their debt obligations, widespread default occurs. The financial system is inundated by a wave of bankruptcies, threatening the survival of the entire system.[xii]

The unrealistic optimism of bankers has led to catastrophe – just like we saw in 2008’s GFC. But as society teeters over this economic abyss, the government then steps in. In the USA, Congress and the Federal Reserve now begin to enact policies that act as ‘circuit breakers’ against the recessionary forces: interest rate cuts, bailouts and quantitative easing (‘QE’). Following these circuit breakers are enacted, liquidity rises, banks avoid insolvency, and hopefully, bankers start lending once again. If so, investment increases, share prices rise, banking profits increase, recession is averted, and economic order is restored. At least, until another crisis hits, and the cycle repeats.

Moral Hazards

If the government is sensible, they then restrict the risky lending that caused the crisis. But if they aren’t, their decision to save the financial sector instead creates a ‘moral hazard’ – that is, they ensure that the parties who profit don’t bear the risks of banking.

Economists have long criticised governments for creating moral hazards after financial crises. Policies such as bailouts and QE teach bankers that risky lending merits no punishment. Indeed, as these policies tend to increase banking profits, they instead support and reward risky lending. So, if the government fails to tighten regulations after they prevent a crisis, their emergency support worsens the bankers’ risk-taking activities. Bankers will now have an implicit guarantee that they will be rescued if their lending causes another crisis in the future.

As ever, bankers remain unable to predict the future of financial markets. And for the most part, prices are still determined by irrational forces. However, by creating this moral hazard, governments can effectively give bankers a guarantee that the future will continue to be profitable – even in crises where real profitability is impossible.

(V) Quantitative Easing 2020

Government power can fix the future, leading to a world where standard economic thought looks like nonsense. Artificial moral hazards can severely distort price behaviour. Already an irrational process, price determination can become absurd where the government commits to saving bankers, no matter what.

We know this; it is no secret. However, moral hazards in financial markets are abundant today. Indeed, in the US, the moral hazard created by the government is so well known that it has an ironic nickname: the ‘Greenspan Put’.[xiii] In essence, the Greenspan Put is the Fed’s unbroken promise to save financial markets whenever a crisis hits, through measures like bailouts, QE and interest rate cuts.

In 2020, the Fed brought the Greenspan Put into play on March 16th, when they began a program of quantitative easing (QE) to support asset prices.[xiv] Between March 9th and June 8th, the Fed purchased toxic assets from banks in earnest, and their balance sheet increased by 69%. In absolute terms, $2.75 trillion of liquidity entered the financial system, an amount than that exceeds all the funds injected by the Fed’s QE program between 2008 and 2012. Banks then used this cash to buy assets from other banks.[xv] Demand for shares increased, and the value of the S&P500 rose 43% while the Fed conducted their short but enormous program of QE.[xvi]

As such, the value of shares did not rise because investors expected profitability to increase: investors expected the Fed to enact the Greenspan Put once again. In February, investors should have expected liquidity to rise dramatically in the coming months. They should have expected share prices to increase as a consequence, leading to capital gains.

So, when the Fed began QE in 2020, the demand for shares rose because a) the money supply increased, and b) because ‘average opinion’ expected ‘average opinion’ to expect prices to grow in the wake of this liquidity injection. Accordingly, investors bought shares and prices rose, confirming their belief.

(VI) Ersatz Capitalism

To sum up the preceding arguments, we will say the following. If we want our expectations of the future to be correct, we have two avenues at our disposal. We can become impossibly good at prediction. Or we can enlist the help of institutions powerful enough to guarantee our profits – no matter what happens.

From this perspective, the share market’s behaviour now makes sense. A belief in future profitability has not driven market returns this year. Instead, the provision of liquidity and the expectation of subsequent asset-price inflation has caused the rise of the S&P500 throughout 2020. It was not rationality or irrationality that increased capital gains; rather, it was government-induced anti-rationality, the moral hazard that has once again given us profits without profitability.

Across the world, there has been over $6 trillion in QE throughout 2020 – more than half of the total QE seen worldwide between 2009 and 2018.[xvii] Accordingly, we will probably see a repetition of the USA’s experience in many other countries. This includes Australia, where the Reserve Bank recently dropped interest rates to 0.1% and announced a $100 billion QE program.[xviii]

In the months to come, we should therefore prepare ourselves for life in this system of ‘ersatz capitalism’. We should expect financial markets to behave like pale imitations of themselves for some time. Forever, perhaps – unless our governments reform the financial sector in favour of stability instead of this strange mode of capitalism.[xix]

(VII) The Price-Earnings Ratio

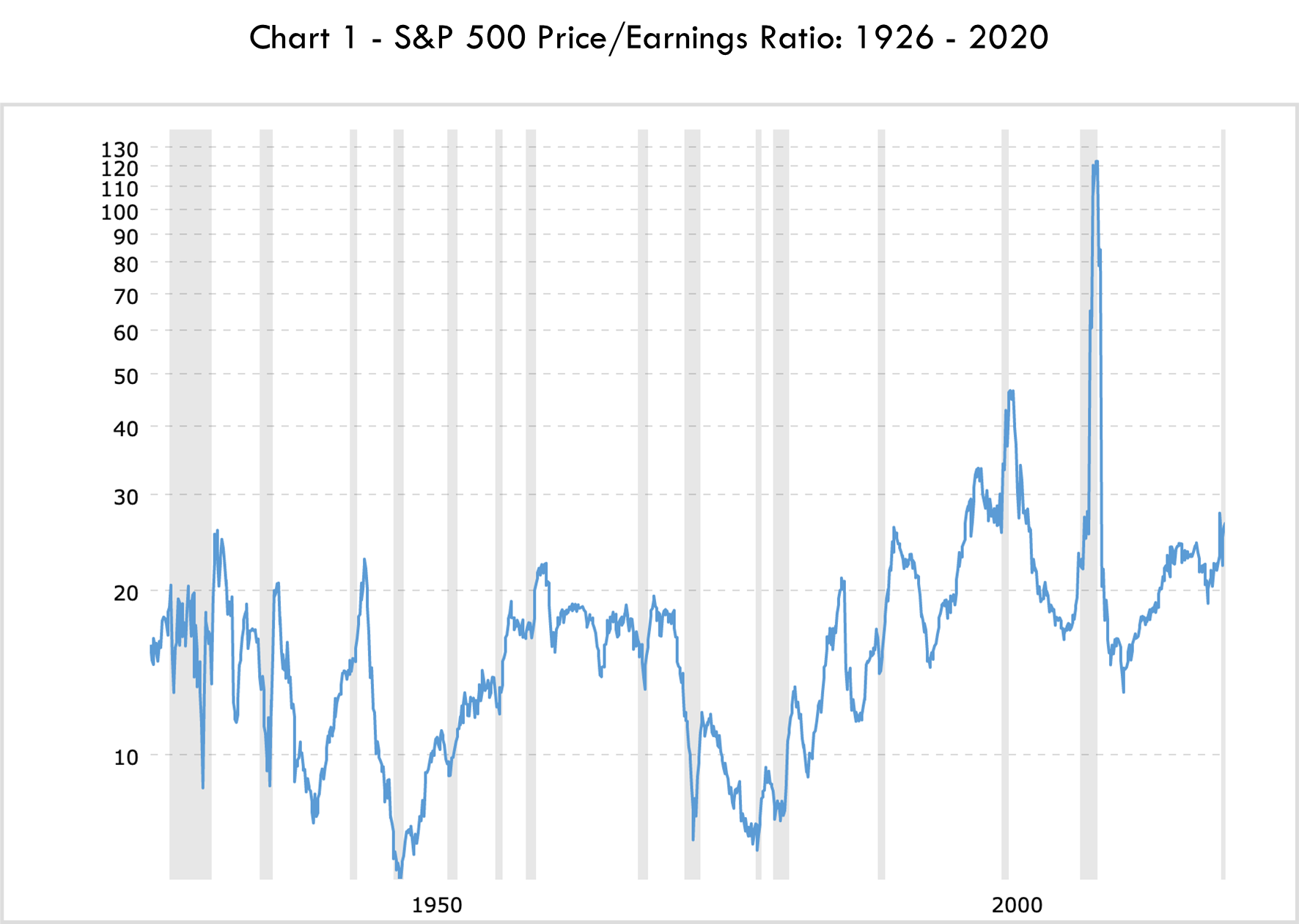

If you are sceptical about this conclusion, you need not take my word for it. The price earnings ratio of the S&P500 (Chart 1) shows us all we need to know. Historically, investors have used the P/E ratio to ascertain whether prices accurately reflect the underlying value of an asset. Mathematically speaking, the ratio rises when earnings fall or prices increase, and it declines when earnings increase and prices fall. If it is too high, this suggests that the asset is overvalued.

Since 1926, the P/E ratio has risen above 25 only a handful of times. It did so in the early ‘90s, again during the dot-com bubble, during the GFC, and now, during the COVID-19 crash. As of December 2nd, it sits at 37.14 – the highest it has been since the 2008 crash.[xx] The times that precede or follow economic crises see the P/E ratio increase dramatically. Of course, this is not because earnings increase during recessions; rather, earnings fall while prices are inflated by government intervention. Both factors conspire to raise the P/E ratio to unprecedented levels. Accordingly, the P/E ratio is not simply a measure of asset valuation: it is now a measure of government interference, and the overall health of financial markets. It is impossible to say what the future will bring; but from our vantage point, markets during COVID-19 look rather sick. Let us hope we can find a way to restore their health.

Recommended Reading

Chapter 12 of Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money is both incredibly illuminating and very short. L. Randall Wray’s Why Minsky Matters is a simple overview of Minsky’s work, which has become indispensable in understanding the dynamics of the financial system that led to the global financial crisis in 2008. Stiglitz’s book Freefall is a good overview of that crisis, and the problem of moral hazard that the Fed has created through their bailouts and quantitative easing programs.

References

Graham, R. J., & Harvey, C. R. 2001. The theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence from

the field. Journal of Financial Economics, 60(2-3), 187-243. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00044-7

Keynes, J. M. 1957. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd.

Massumi, B. 2018. 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value: A Postcapitalist Manifesto. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stiglitz, J. 2010. Freefall: America, Free Markets and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Varoufakis, Y. 2015. The Global Minotaur: America, the True Causes of the Financial Crisis and the Future of the World Economy. London: Zed Books.

Vogl, J. 2014. The Specter of Capital. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Wray, L. R. 2016. Why Minsky Matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Endnotes

[i] See https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/coronavirus-recession-worst-wwii-economic-recovery-global-deutsche-bank-2020-3-1029012757?utm_source=msn.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=msn-slideshow&utm_campaign=bodyurl#

[ii] See https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/us-gdp-drop-record-2q-amid-coronavirus-recession-goldman-sachs-2020-3-1029018308?utm_source=msn.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=msn-slideshow&utm_campaign=bodyurl

[iii] See https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gross-domestic-product. When the BEA released this statistic in July, it also had no discernible effect on financial markets.

[iv] A recent report on New York’s securities industry confirms this reversal of fortune. Their profits between January and the end of June in 2020 totalled $27.6 billion – only slightly less than the total profits earned in 2019. See https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/osdc/2020/pdf/report-6-2021.pdf

[v] See Freefall: America, Free Markets and the Sinking of the World Economy.

[vi] On page 152, Keynes writes: ‘In practice we have tacitly agreed, as a rule, to fall back on what is, in truth, a convention. The essence of this convention – though it does not, of course, work out quite so simply – lies in assuming that the existing state of affairs will continue indefinitely, except in so far as we have specific reasons to expect a change.’ This convention allows us to attain ‘a measure of continuity and stability in our affairs, so long as we can rely on the maintenance of the convention.’

[vii] While this convention sounds ridiculous, it remains prevalent today. Popular financial models, such as the Black-Scholes model and the CAPM formula,a are usually implemented using historical data to estimate future prices. This means investors using these models like this assume the future will look like the past, even though crises like the dot-com crash, the GFC, and the COVID-19 recession show that this convention has failed dramatically on three occasions in under 25 years. Lacking clairvoyance, we have little besides this belief; hence, our meagre powers of prediction make asset pricing irrational.

a Studies show that financial analysts regularly use both formulas. A famous 2001 study by Graham and Harvey found that 74.9% of the 392 CFOs surveyed used CAPM ‘always or almost always’.

[viii] The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money, pp. 154 – 156.

[ix] The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money, pp. 161 – 163. See also: Brian Massumi’s 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value.

[x] The words are Keynes’, quoted in Massumi’s 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value.

[xi] Why Minsky Matters, p. 86.

[xii] Wray explains it like this: High aggregate demand and high profits associated with full employment raise expectations and encourage increasingly risky ventures based on commitments of future revenues that are too optimistic. When the expected revenues are not realised, a snowball of defaults then leads to debt deflation (debtors default on their debts, which are assets of creditors) and high unemployment. See Why Minsky Matters, p. 86.

[xiii] Named after former Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, this epithet has an interesting history.

During the 1987 stock market crash, Greenspan affirmed the Fed’s commitment to ‘serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system’whenever a crisis hit. Here, Greenspan gave the market certainty: he would use all his powers to ensure the stability and profitability of an increasingly volatile and fragile system. From this point onwards, investors could rely on the Fed to bail out banks and refloat the financial economy if problems arose. Greenspan repeatedly lived up to his promise, so his commitment became known as the ‘Greenspan Put’.

Under Greenspan’s leadership, a financial crisis would always cause the Fed to buy assets at a good price. His successors have dutifully followed suit, starting with Obama’s Fed Chair, Ben Bernanke, who bailed out the banks during the GFC. And now, during the COVID-19 economic crisis, Jerome Powell has exceeded his forebears in every regard.

See: https://www.federalreserve.gov/Pubs/feds/2007/200713/200713pap.pdf

[xiv] In 2008, the Fed also justified their actions via a mode of ‘trickle-down’ economic thought. The argument is that QE depresses long-term yields relative to short-term yields. This incentivises the borrowing of debt, which is then used for investment, creating jobs, income growth, etc., supporting the wider economy. There is also a consumption wealth effect: investors who make greater returns will spend their dividends etc. in the economy, stimulating growth. Some economists were highly critical of this mode of argumentation, saying that it created a dangerous asset bubble that did little for economic growth.

[xv] In general, QE can only be used to buy paper assets from other banks. It cannot be used for loans, etc., and hence, it does not cause inflation.

[xvi] Of course, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Stimulus Act 2020 contributed to this rise: announced on March 28th, this package, which was three times larger than Obama’s GFC stimulus, pumped another $2.4 trillion into the economy.

[xvii] See https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/global-qe-asset-purchases-to-reach-usd6-trillion-in-2020-24-04-2020

[xviii] See https://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2020/mr-20-28.html

[xix] An afterthought: to call this system capitalism at all, ersatz or not, doesn’t seem radical enough. What we have cannot be called a ‘poor imitation’ of capitalism, because it has nothing to do with capitalism at all. At its most basic level, capitalism is a system of privately owned, risk-taking firms, united by a commitment to generate profits through competitive, real production. The value of a company in a capitalist system, as revealed in its share price, should reflect their success in these regards.

But due to the Fed’s commitment to QE, for at least a few months this year, information about profitability and production became irrelevant to our financial markets. As the crisis unfolded, share prices were severed from underlying economic performance. The value of companies became disconnected from their successes as capitalist institutions. In 2020, financial returns were not based on ingenuity or skill: they were secured by the brute force of the government.

The government intervention that has produced this dangerous mode of moral hazard has completely changed the logic underlying asset pricing. Our expectations of profitability are divorced from those concerning volatility, capital gains, returns, etc. Capitalist logic no longer governs our financial markets. They are not even ersatz capital markets: and so, we need a new word to describe our system today.

[xx] See https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-pe-ratio

Modern Monetary Theory

By A. F. Cannon

As our leaders look to repair our economies after the COVID-19 crash, a wild new way of economic thinking has surged to prominence: modern monetary theory, or MMT for short. MMT’s supposedly radical ideas for money creation and government spending have caused fear and confusion. ‘It’s dangerous,’ we hear. ‘We’ll end up like Zimbabwe!’ we’re told. Debt crises, financial ruin – or, perhaps, the chance for a better future. All this angst is intriguing. So, let’s take a closer look at MMT.

THE PATH TO MMT

The rise of MMT started after the global financial crash in 2008. As Netflix’s film The Big Short shows, bad financial modelling, systemic malpractice, and underestimating risk caused a collapse of the banking system. Blatant and severe problems in the financial sector grew unchecked, and eventually, the whole thing exploded. Remarkably, almost nobody saw the crash coming. Alan Greenspan, former Fed Chair and ‘greatest central banker in the history of the world,’1 was dismayed. He said the ‘whole intellectual edifice’ underpinning our financial markets had collapsed. Unable to understand its own flaws, contemporary economic and financial modelling lost its credibility during the crisis: the crash bankrupted it, alongside Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.2

After the GFC, we needed a new way to think about economics. We were desperate for a new paradigm that avoided the fatal flaws of the old ways of thinking. Over the last decade, people worldwide have laboured hard to meet this demand, and several of their ideas have become prominent. Some of them are quackish, others are underwhelming, but a few have promise.

Modern monetary theory has been the most successful and the most controversial of these ideas. Until recently it was an academic obscurity, but now it has gone mainstream. Politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have adopted MMT-inspired policies. Leading theorist Stephanie Kelton’s recent book, The Deficit Myth, has also been widely acclaimed. These figures are all highly visible in the media, where they regularly make surprising calls for policy change. They say we need a ‘universal job guarantee’ and a ‘Green New Deal’, both financed by – what? – printing money. That’s right. Printing money.

WHAT IS MMT?

At the moment, there is no consensus on MMT. Depending on our source, MMTers are either charlatans or savants; they are profoundly pragmatic or dangerously utopian. Some say Kelton’s work is ‘on a par with the genius of DaVinci and Copernicus’. Others simply tell us MMT is ‘dead wrong’. And a poll of leading economists like Angus Deaton and Daron Acemoglu suggests the academy is overwhelmingly against it.3 There is some potent opposition to MMT, then. But if we read what MMTers themselves have to say, it’s hard to see why it inspires these extreme responses.

According to economist James K. Galbraith, MMT is just ‘a description of how a modern credit economy actually works’.4 While its arguments might be surprising, they aren’t illogical. In essence, the theory tells us that governments with their own currency don’t need money reserves or tax revenues before they can spend. After all, the government is always the source of money in the economy. Logically, taxation can’t occur before money creation. Instead, the government has to create money ex nihilo – ‘from nothing’ – and spend it into existence before receiving their tax revenue. The whole monetary system doesn’t make sense otherwise.

‘From nothing?’, you say. Yes: from nothing. MMT says money only exists because the government creates it from nothing. ‘How does this work?’ you ask. Well, it’s pretty simple. First, the state uses its power to impose taxes on its people. Then, it demands payment of these taxes in the currency it issues. Workers and producers then find that they need government currency, and they get it from a combination of government spending and private lending. Once they have the money, they pay taxes on a portion of their output, and they keep the rest. The government gets its tax, and the workers use the remaining money for investment, consumption, etc.5

All this leads us to a new take on government deficits. As taxes are never equal to 100% of output, the government initially falls into a budget deficit. They can’t tax away dollars that they haven’t spent first. The government, then, can only achieve a budget surplus if the private sector is in deficit. To run a surplus, the government has to reduce money creation, pull existing money out of the system by raising taxes, or seek loans from the private sector.6 Accordingly, the government doesn’t need to finance their deficits through borrowing. For them, reasonable, perpetual deficits are a sign of a healthy economy. Budget surpluses, on the other hand, impede economic growth by draining resources away from private investment. Worse still, surpluses frequently precipitate periods of crisis, as the private sector engages in risky lending to finance the government.7

If all this is true, it has some important implications for government policy. MMTers tell us that countries who:

- a) hold a sovereign currency (in MMT-speak, a fiat currency that isn’t convertible into something the government can run out of, like gold or foreign currency), and

- b) who borrow only in that currency,8

can and should issue money to create ‘a full employment economy.’9 According to MMT, a government can spend money into existence to bring the economy to its productive capacity. It also says that countries using a sovereign currency can’t default on their obligations. As Galbraith tells us, countries like Australia and the USA are ‘not Greece, and cannot become Venezuela and Zimbabwe’. Incidentally, Warren Buffet and Alan Greenspan agree:10 a country with a sovereign currency can always finance its deficits by creating currency. We can’t run out of our own money.

THE CASE AGAINST MMT

For those weaned on monetarism – practically everyone reading this article, myself included – this sounds like pure anathema. Isn’t ‘inflation always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’?11 Won’t printing money to fund our deficits lead us to ruin, Argentinian style? Mainstream economists – none of whom foresaw the GFC in 2008, by the way – seem to think so.

For Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff, these ideas on deficits are ‘just nuts’. In his view, this ‘modern monetary nonsense’ forgets that the ‘printing press is not a panacea’, as its use can lead to problems with debt repayment and currency demand. Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman tells us he doesn’t ‘understand [MMT’s] arguments at all’. Elsewhere, he expresses ‘mild concern’ over the MMT position ‘that because we have a printing press deficits don’t matter’. Lastly, for Larry Summers – Yanis Varoufakis’ very own ‘Prince of Darkness’ – MMT is ‘voodoo economics’ and a ‘recipe for disaster’. It offers ‘the proverbial free lunch’, he says, ‘the ability of the government to spend more without imposing any burden on anyone.’

The fearsome free lunch, people: be afraid.

Economists hate free lunches. We know this. We all agree that a free lunch is the worst kind of lunch. Today, no serious economist argues for policies that try to give people something for nothing. History tells us this is usually disastrous. We know that printing money to finance expenditure will cause inflation. Government’s credibility will decline. The costs of borrowing will increase, and the currency’s value will fall.12 We know there is nothing desirable about printing endless piles of money – ‘keystroking’ it into existence with computers, as MMTers say. And we know that countries around the world have ruined themselves by pursuing this strategy.

THE CASE FOR MMT

It is lucky, then, that MMT proposes nothing of the kind. Stephanie Kelton is at pains to reassure us: ‘MMT is not a free lunch’, she says throughout her Deficit Myth. Galbraith also tells us he knows of no MMT advocate so naïve as to say that ‘deficits don’t matter’. Along with the MMT community at large, Kelton and Galbraith understand that governments looking to spend must be sensitive to our economy’s real resource constraints.

Proponents of MMT don’t advocate for unlimited money printing. Instead, they argue that the government can spend money until all the economy’s real resources are used in productive activities. The economy has real constraints, a point Kelton makes at least seven times in her book. She also emphasises that ’failing to identify – and respect – those limits could bring great harm’ to our economy’ in the form of inflation.13 Like all economists, MMTers say governments can spend money to push the economy to its productive limit. Unlike others though, they also say governments should do this. That it’s their responsibility to spend until we hit full employment.

INSIGHT

As we have seen, MMT purports to offer a compelling solution to our economic problems. But do its arguments stack up? And will it work?

When I think about the viability of MMT, I have to remind myself of a few facts. Since my birth in 1994, our society has lived through the rupture of the dot-com bubble in 2000. Next, we saw the global financial system collapse in 2008. Then, the Eurozone crisis persisted through the 2010s. Now, we’re in a recession caused by the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020. Over this period of crises, interest rates and capital investment measured as a share of GDP have fallen to historic lows in many countries, taking economic growth down with it.14 Over my life, economies worldwide have become more ineffective, partly because of our way of thinking about economics. We need to change. Maybe, MMT is the winning idea.